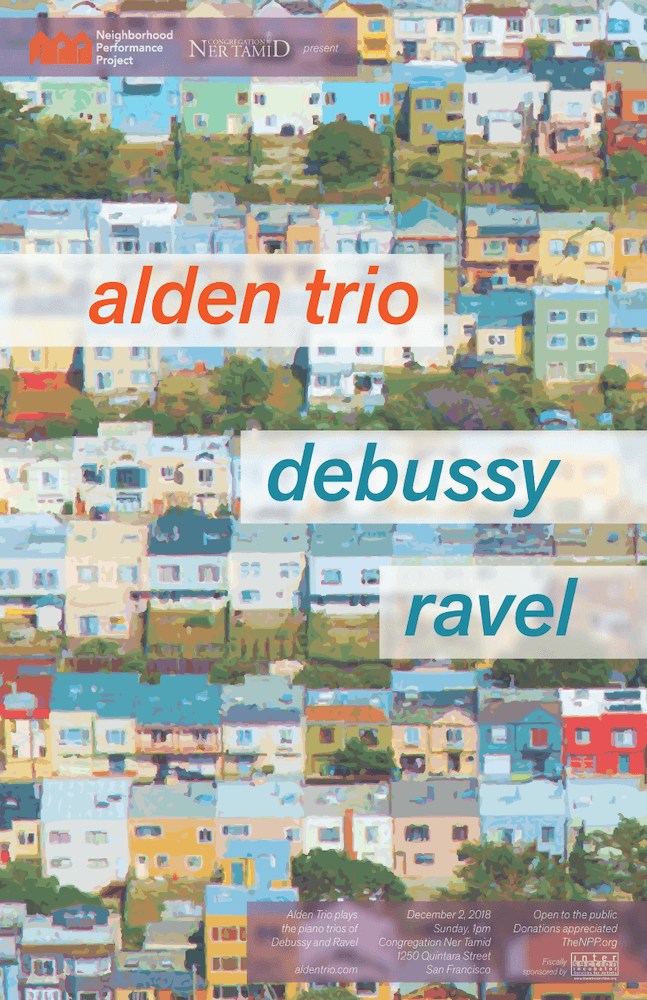

Debussy Ravel

presented by Neighborhood Performance Project and Congregation Ner Tamid

public performance donations welcome

-

December 2, 2018

1 pmCongregation Ner Tamid

1250 Quintara Street

San Francisco, CA

Debussy Piano Trio in G major, L. 5Ravel Piano Trio in A minor

The Alden Trio present a French program of trios by Debussy and Ravel.

Debussy Piano Trio in G Major, L. 5

In 1872, at the age of ten, Debussy entered the Paris Conservatoire. There his piano teacher, Antoine Marmontel, noted his first prize in score-reading and recommended him to Nadejda von Meck, the famous patroness of Tchaikovsky, who was looking for a pianist to accompany her and her children on their travels.

He joined her in the summer of 1880, when he administered piano lessons to her children, accompanied her daughter who was a singer, and played piano duets with herself. They arrived in Florence that fall, where the family was joined by a violinist and cellist fresh from the Moscow Conservatory. It seems the trio was required to perform every evening. Tchaikovsky had not yet written his tragic Trio in A minor; the young Debussy, eighteen at the time, beat him to it and wrote his own Trio in G major. Perhaps this served as inspiration for Madame von Meck, who asked Tchaikovsky for one.

The Trio reflects Debussy’s criticism of German music as being “too heavy and clear.” As early works go, it appears to reflect the composers familiar to Debussy at the time—Delibes (whose music was ubiquitous at the Conservatoire’s sight-reading class), Franck, Schumann. The work can’t be characterized as anything but lightweight salon music, written for immediate gratification.

The piece appears in four movements. The first movement tends to have four-bar phrases that take a seat at the end waiting for something else to happen; while a weakness here, it is a feature Debussy uses effectively in his later music. The playful second movement hops between dainty and smooth textures, conjuring images of tutus and a Pas de deux. The third movement’s romantic expression evokes a swan solo. The Appassionato finale provides a strong end to the work.

The existence of the trio was known and catalogued but assumed lost. An autograph score of the first movement and the complete cello part became available in 1980, but it wasn’t until an autograph score of the last three movements was discovered among the papers of Debussy’s pupil Maurice Dumesnil two years later that the entire trio could be assembled. The effort wasn’t without its challenges: the two sets of autographs has considerable discrepancies between them, suggesting different drafts; an entire page from the score of the finale was missing and had to be reconstructed; and amusingly, Dumesnil had physically removed the last four measures of the finale and gifted it, through he at least had the good sense of copying the score of these measures on the scrap. The reconstituted trio was published by Henle in 1986.

Ravel Piano Trio in A minor (1914)

I think that at any moment I shall go mad or lose my mind. I have never worked so hard, with such insane heroic rage.

Ravel

The source of Ravel’s rage was the dawn of World War I, and the output of his labor was his Piano Trio. In composing the Trio, Ravel was aware of the compositional difficulties posed by the genre: how to reconcile the contrasting sonorities of the piano and the string instruments, and how to achieve balance between the three instrumental voices, especially since the cello often is not heard as easily. Ravel addressed this problem by taking an orchestral approach, using the extreme ranges of each instrument, creating rich textures and effects with trills, harmonics, and arpeggios. To achieve clarity in texture and secure balance, Ravel frequently spaced the violin and cello lines two octaves apart, with the right hand of the piano playing between them.

Inspiration for the musical content of the Trio came from a wide variety of sources. In the opening movement, Modéré, Ravel evokes the Basque music from his native region by using an irregular 3+2+3 meter. The Pantoum of the second movement refers to a form of verse used in Malaysian poetry, where the second and fourth lines of each four-line stanza become the first and third lines of the next. The third movement, a stately Passacaille reflecting Baroque techniques, is a haunting set of ten variations progressive in their intensity until the seventh one. The Final is orchestral in nature, containing many references to Ravel’s Spanish influences.